Overlords: Part 6. The Labs — Building the Post-Democratic Stack

How live regimes became laboratories for the convergence code behind post-democratic governance.

The first five articles in this Overlords series traced the transition of governance from democratic ritual to protocol-driven control. Part 1 exposed electoral theatre as scripted compliance. Part 2 mapped the layered logic of behavioural enforcement. Part 3 detailed soft law's override of sovereignty. Part 4 tracked the conversion of identity into access. Part 5 revealed the genetic gating of the human subject.

This sixth instalment shifts from architecture to assembly. It argues that what we now call the Overcode—a convergent runtime logic of control—emerged not all at once, but through real-world testbeds. These labs of history did not produce uniform outputs. But they trialled, refined, and embedded control structures that now scale as global infrastructure.

This is not conspiracy. It is structural mimicry. Regimes facing crisis or opportunity reached for control architectures that proved operable elsewhere. Patterns emerged—repeatable, optimisable, exportable.

Analysts like Patrick Wood correctly identified technocracy not as policy trend but as systemic drift. Wood tracked the rise of technocracy from 1930s fringe ideology to 21st-century operational standard. From Technocracy Inc. to the Rockefeller–Brzezinski configuration, to Trilateral coordination and sustainability mandates, the pattern holds: elite consolidation via expert filtration, bypassing democratic process. He identified not merely actors, but interfaces—where ownership and oversight uncoupled.

My own time in Singapore during the early 1970s confirmed this logic on the ground. The British military had departed. Australian and New Zealand units remained as transitional defence scaffolding. By then, the signs were literal: No Spitting. No Littering. $1000 Fine. High-rise public housing was replacing kampongs around the island. Democracy was already absent—its absence defended by those around me. Jailing the opposition wasn’t hidden. It was celebrated. Obedience, cleanliness, containment: all visibly staged as civic virtue. What I saw then now reads differently. Not as anomaly, but as prototype.

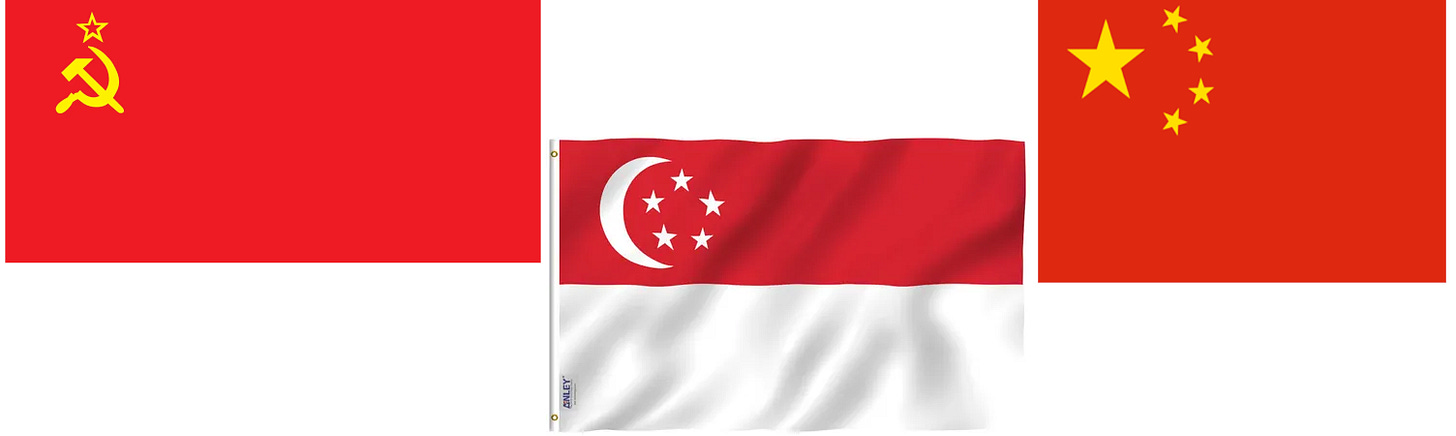

This article does not offer an origin myth. It reconstructs governance as iterative assembly—across Soviet industrial trauma, Maoist firmware programming, and Singapore’s urban compliance grid. Each operated as a lab. Each left artefacts now scaled. Not as doctrine—but as executable form. What links them is not command, but system inheritance.

The Soviet Control Stack Genealogy: Compliance Through Catastrophe

The Soviet Union began as a revolution and ended as a system. In 1917, the Bolsheviks rode a wave of grassroots uprisings—workers’ soviets, peasant councils, land committees—many of which operated autonomously in the chaos of tsarist collapse. There was genuine bottom-up ferment, improvised governance, and ideological diversity. It didn’t last. By 1921, the horizontal phase had been overwritten. Lenin’s consolidation and the New Economic Policy marked a pivot: revolutionary pluralism was replaced by state capitalism administered through the Party. Trotsky’s dream of permanent revolution was discarded for command hierarchy. The soviets were formalised, standardised, and rendered subordinate. Behind the revolutionary theatre, Lenin’s return to Petrograd was bankrolled and brokered by the German General Staff. Western banks, particularly through intermediaries like Sweden’s Olof Aschberg and institutions like Guaranty Trust, established financial conduits with the new regime. This return must be considered as simultaneous grassroots energy and elite instrumentalisation, where the banks were not making ideological endorsements, but strategic bets. Capital understood that a closed system of economic command could be useful as a guarantor of risk free profitability.

Marx and Engels had proposed a full-scale re-engineering of society. The Communist Manifesto outlined the abolition of the bourgeois family, centralisation of credit, and compulsory state schooling. Under Stalin, selective uptake of revolutionary theory was used tactically so that Stalin’s state didn’t abolish the family, it redefined it. The collectivised family, bureaucratised reproduction, and schooling-as-firmware defined the Soviet formatting stack. The “New Soviet Man” was not born but compiled—via surveillance, deprivation, and instructional override. Programmability, not freedom, was the design vector.

And yet, the USSR achieved something staggering. It took a largely illiterate, agrarian, post-serf population and, within a generation, built an industrial base capable of defeating Nazi Germany. It built steel plants, hydroelectric dams, and mechanised agriculture from nearly nothing. The literacy rate jumped from below 30% in 1917 to over 85% by the late 1930s. Engineers, doctors, and factory technicians were trained at scale. When the Wehrmacht invaded in 1941, the USSR absorbed the shock and relocated over 2,500 factories east of the Urals. By 1943, it was outproducing Hitler’s war machine in tanks, artillery, and aircraft. Albeit at huge cost of somewhere up to 27 million by the war’s end, the command economy worked—not as a market, but as a logistics engine. That infrastructure and the logic behind it, built for wartime throughput and shielded from market volatility, never fully disappeared. Those relocated plants and concept of latent wartime capability laid the industrial skeleton for Russia’s military resurgence in the Ukraine war since 2022, so that by 2025 Russia is outproducing not just Ukraine but the entire collective industrial base of NATO.

Notwithstanding it’s achievements, the soviet engine ran on forced sacrifice. Collectivisation killed millions. The gulag became not just a penal system but a labour force. Industrialisation was driven by expropriated grain, imported machinery, and coerced bodies. American firms—Albert Kahn Associates, Ford, General Electric—supplied factories and training. The USSR’s first Five-Year Plans were not autarkic. They were coded hybrids of Western industrial logic and total command governance. The question was: could central planning rewire society as infrastructure?

Education was the compiler—but it did not operate alone. While Soviet education was highly ideological, it produced a wealth of genuine scientific and technical expertise. That said, the Soviet project combined schooling with systematic dislocation so that entire populations were uprooted and resettled, not just for economic planning, but as a tool to erase inherited identities. National minorities, dissidents, and suspect classes were deported en masse—from the Volga Germans to the Crimean Tatars—fragmenting cultural continuity and seeding compliance. By the late Soviet period, the USSR had produced the largest technocratic class on earth—bureaucrats fluent in inputs and outputs, who thought in protocols, not politics. The aim wasn’t education as enlightenment—it was to overwrite the past and render a new operational subject. Forced migration wasn’t just a trauma—it was a formatting tool.

What appeared as stagnation in the 1970s was, in structural terms, saturation—followed by epistemic self-collapse. The system had no tolerance for failure, and even less for admitting it. Metrics became rituals. Quotas were met only on paper. No official could afford to acknowledge what was plainly visible: the machine was still running, but the code had stopped updating. Truth became dangerous so that to speak of inefficiency was to imply sabotage. The KGB and affiliated secret police managed this collapse not through brute force alone, but through anticipatory containment: predictive profiling, social graphing, ideological heat-mapping. The original Berlin Wall, contrary to Western mythology, was initially designed to protect the borders from the fallout of Western economic destabilisation and exploitation of West Germany—yet it became a containment perimeter for its own population. The borders faced inward.

Deviance was pre-empted, not punished. Where ideology lacked traction, psychiatry filled the gap. Diagnosis became the protocol of deviation management— “sluggish schizophrenia” and “philosophical intoxication” functioned not as treatments but as containment tags. The system did not penalise dissent—it reclassified it. Identity was not merely assigned; it was interrogated, rewritten, and, if necessary, erased. Political heresy became a clinical symptom.

When the USSR collapsed in 1991, it was not overthrown. It expired. Belief drained out, but the infrastructure held. Protocols remained in place, even as the ideological scaffolding disintegrated. But the fall did not mark the start of liberation—it marked harvest. Western financial institutions, led by the IMF and World Bank, descended with “reform packages” that gutted what remained of the state. Industry was sold off at cents on the dollar. Natural resources were privatised into oligarchic monopolies. Western banks underwrote the pillage, local elites took the spoils, and the population bore the consequences. Life expectancy plummeted. Male mortality surged. Alcoholism soared. Pension systems collapsed. Medical services degraded into pay-to-play. All sectors of public life—education, transport, health—deteriorated, except for those captured by post-communist oligarchs. It was not a peaceful transition. It was a controlled demolition followed by asset extraction.

The core lessons of control had already been harvested long before the USSR’s formal collapse in 1991. A key piece of evidence is the 1984 interview between Yuri Bezmenov (alias Tomas Schuman), a former KGB propaganda operative, and American journalist G. Edward Griffin. In that interview, Bezmenov explicitly describes the Soviet strategy of ideological subversion—a four-stage process designed to demoralise, destabilise, create crisis, and then normalise a society under new control structures. He claimed these techniques were not isolated to Soviet geopolitical expansion but were already being mirrored and adopted in the West.

The interview predates the Soviet Union’s implosion by nearly a decade. Bezmenov's core thesis: the tools of cultural and cognitive capture had already been internalised by Western elites. In these terms, conquest of the West did not need tanks or coups—it already had universities, media, and policy foundations running imported Soviet logic under liberal aesthetics.

In the end, the USSR functioned as a demonstrator—a high-friction prototype for population control, the real innovations of which were quietly absorbed by its supposed enemies.

China: From Traumatic Mirror to Exportable Myth

Maoist China reenacted the Soviet protocol as a scaled trauma ritual. The Great Leap Forward (1958–62) emulated Soviet collectivisation—central planning, grain requisitioning, engineered famine—killing an estimated 30–45 million. The Cultural Revolution (1966–76) then acted as ideological firmware purge: kinship erased, authority inverted, history deleted by weaponised youth. Both phases were less about governance than sacrificial reformatting. The Party broke the past to install a new operating logic.

To understand China’s control model, one must grasp its cultural substrate. The CPC did not inherit the divine right of kings, nor liberal notions of popular sovereignty. Its authority is more accurately traced to a secularised Mandate of Heaven—a conditional, performance-based legitimacy deeply embedded in Chinese political memory. It governs not by permission, but by proof. Where the soviets had the Communist Manifesto, Mao’s innovation was his Little Red Book not unlike the transition from prophecy to catechism. Where the Manifesto promised historical inevitability, the Red Book enforced present-tense fidelity. It did not interpret the future. It performed the Party. These two documents can be seen to represent two different stages of ideological software: one a speculative architecture, the other an executable interface. Marx and Engels, writing in 1848, laid out a vision of historical inevitability—class struggle as the motor of history, the bourgeoisie as its transient apex, and the proletariat as the agent of its final overthrow. A century later, Mao’s Little Red Book served a different function. It did not theorise history—it synchronised behaviour. Compiled in 1964 by the People’s Liberation Army’s General Political Department, the book was a selection of Mao’s speeches and writings, edited into aphorisms and distributed en masse. It was not written to persuade the enemy class. It was built to format the believer.

In this context, the Little Red Book functioned as operational code during the Cultural Revolution. Carried, recited, and deployed in struggle sessions, it served as both epistemic firewall and behavioural filter. Where the Manifesto projected historical law, Mao’s book enforced immediate compliance. Every quote was an executable command. Every slogan a test of alignment. Ideology became biometric—measurable through gesture, repetition, and enthusiasm. Where Marx framed revolution as historical necessity and Trotsky projected it as a global continuum, Mao retooled it as an internal purge cycle—ideology as self-correction loop. His version of class struggle never ended; it was recursive, purgative, and internalised.

Mao’s Little Red Book functioned much like scripture—recitation, memorisation, and public display were mandatory. But this was scripture without metaphysics: a state-authored catechism engineered to overwrite tradition, sever lineage, and install allegiance. Where religious texts encoded cosmological order, Mao’s booklet enforced epistemic closure. The divine was replaced with the dialectic. Its purpose was not spiritual formation but behavioural standardisation—compliance through citation. During the Cultural Revolution, it became a ritual object, carried by Red Guards, waved in denunciations, and used as a calibration signal of ideological hygiene. The book’s content mattered less than its ubiquity: it instantiated Mao’s authority into the hands of millions, reducing politics to a protocol of repetition.

The Little Red Book’s legacy lives on not in Marxist slogans, but in informational form. It was the first mass-distributed firmware of ideological control—a portable compliance interface designed to collapse cognition into obedience. Its symbolic logic reappears in digital loyalty apps, social credit dashboards, ESG metrics, and institutional pledge rituals. It was not a doctrinal anomaly. It was an early beta test for cognitive standardisation—refracted through the screen and scaled globally.

After Mao, Deng Xiaoping executed a core-level patch. He dropped belief and installed access. The state did not liberalise—it abstracted its control stack. Special Economic Zones (SEZs) became runtime interfaces where capital entered on CPC terms. The pivot began with Kissinger’s 1971 visit, which reinitiated protocol exchange between East and West. By the time China joined the WTO in 2001, it had positioned itself not as an ideological outlier, but as a disciplined node in the global supply chain. Western capital migrated. Manufacturing, labour, and entire production networks were offshored into CPC-regulated zones, where control and profit aligned. Prosperity was now possible—but only through stack compliance. Legal predictability, cheap labour, IP discipline: these were marketed, but bounded. Control moved from overt repression to calibrated permissioning.

In this frame, the market was not a concession. It was a containment layer—engineered to feed the West’s hunger for cost-efficiency while preserving the Party’s grip on access, process, and escalation. But this convergence was no theft. China did not “steal” jobs, IP, or industrial capital. These were offshored deliberately—transferred by the elite custodians of Western finance as part of a broader strategic pivot from production to speculation. While Western elites financialised their economies—swapping labour markets for asset bubbles—China absorbed the abandoned infrastructure, trained the replacement workforce, and stabilised the output stream. American consumers didn’t resist. They bought Chinese goods with credit securitised against their own homes. Property inflation financed consumption. The working class became debtor class. The CPC didn’t undermine the West—it operationalised its externalities. What looked like competition was closer to orchestration: the Party administered the factory while Wall Street monetised the spread. This was not globalisation. It was convergence theatre—capital upstream, control downstream. From capital conditionality to behavioural modulation, the logic of access extended beyond economics. It was only natural that the same principle—permission over persuasion—would migrate into civic life

This shift—where control appears ambient, not enforced—marks China’s most sophisticated export. Just as the market was reframed as containment, surveillance was reframed as spectacle. The logic of Mao’s Little Red Book—compliance through ritual, repetition, and visibility—was recoded into the architecture of modern governance. But where Mao’s catechism required recitation, today’s control stack operates through ambient threat. It doesn’t demand belief. It demands anticipation. In this schema, the apparatus needn’t function flawlessly. Its credibility depends not on integration, but on projection.

Surveillance in China functions less as an instrument of total visibility than as a theatre of retained legitimacy. Contrary to propaganda narratives, the CPC never built a seamless panopticon—only the simulation of one. Behavioural compliance is driven not by certainty of surveillance, but by its ambient possibility. Citizens act as if watched, because the structure implies they might be. This performative uncertainty disciplines more effectively than any total system could. In reality, the architecture comprises a fragmented lattice: regional pilots, financial blacklists, commercial ratings, biometric trials. Yet the illusion of integration sustains a form of epistemic authority—what matters is not actual omniscience, but projected infallibility.

Western media amplified this mirage, turning infrastructural patchwork into a vision of digital totalitarianism. But this wasn’t critique—it was aspirational transposition. Conditional access, behavioural scoring, algorithmic morality—these features aligned neatly with Western noocratic instincts. What appeared as Chinese repression doubled as Western prefiguration. Research into polygenic educational scores (e.g., Plomin, 2018) and biometric gating of school entries confirm the architecture’s viability as anticipatory input for conditional access regimes—bio-cognition as eligibility interface..

In this schema, surveillance is no longer about enforcement. It is legitimacy theatre—reinforcing a system where prosperity justifies control, and visibility simulates consent. The Mandate is no longer granted from above. It is retained from below—via performed compliance and the absence of collapse. The panopticon need not function perfectly. Its credibility lies not in function, but in presumption.

In that space, where projection replaces implementation, Western elites found a prototype: programmable civics cloaked as administrative foresight. Western institutions did not reject China’s apparent command logic. They inducted it. The World Bank praised the ‘poverty reduction miracle.’ The IMF helped coordinate fiscal harmonisation. WTO accession in 2001 marked full system docking. The UN mirrored five-year plans in its SDG frameworks. The WHO adopted CPC-style containment during COVID. The WEF platformed Chinese executives as global co-architects. Beijing was no longer an outsider. It became a node in the global governance graph. The CPC’s system was not just tolerated—it was admired, studied, and strategically emulated.

China did not replace the Soviet model. It refined it—reducing friction, adding modularity, and cloaking it in prosperity optics. Control became scalable, not through repression, but through permissioned integration with capital and global governance. Western banks funded the rise. Global institutions baptised it. Elite consensus shifted from liberal evangelism to convergence admiration. The CPC never needed to perfect the system. It only needed to run a convincing prototype. And it did. The result is not Chinese dominance—it is system confirmation. What began as ritual control now circulates as governance best practice. The myth became the interface.

Singapore: The Legible Micromodel

Singapore’s path to technocratic statehood began not with Lee Kuan Yew, but with its positioning—first as a British imperial outpost, then as a strategic spoil of war. Captured by the British in 1819 and formalised as a Crown colony in 1867, it served as a maritime choke point at the Straits of Malacca, controlling vital trade between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific. That position made it both prize and target. In 1942, Singapore fell to the Japanese in a collapse that stunned the British Empire. The subsequent occupation was brutal: mass executions, forced labour, cultural humiliation. The trauma lingered. British rule returned after the war, but its legitimacy never recovered. Lee Kuan Yew, after the People’s Action Party (PAP) in 1954 to advocate for self-rule, became prime minister after this was granted in 1959. A brief merger with the Federation of Malaya followed in 1963—but ethnic tensions and policy disputes led to Singapore’s expulsion and full independence in 1965. From that rupture, Lee began the construction of a state unlike any other in the region—not post-colonial in aspiration, but post-democratic in structure.

Lee Kuan Yew’s rise to power in post-colonial Singapore was shaped by both his personal vision and the enduring legacies of both British colonialism and Japanese occupation. His early legal education at Cambridge and later at the London School of Economics (LSE) exposed him to Western liberal thought, including the Malayan Forum, a group of Malayans (as Singaporeans and Malaysians were then known) studying in Britain. The forum provided a platform for discussing political and social issues related to Malaya and Singapore. Proximity to liberal organisations also resonated—Lee absorbed the planning instinct, not the egalitarian ethos. Yet it was the traumatic history of British withdrawal and Japanese occupation that solidified his resolve to control Singapore's destiny through technocratic means.

Lee’s overarching ambition was not merely to govern, but to forge a new society out of the chaos of post-colonialism. His vision for Singapore was shaped by a conviction that democracy, in its traditional sense, was impractical for the city-state’s survival. The British colonial structure had left a fragmented society behind—ethnically diverse and marked by stark economic and social divisions. Lee was not a democrat; he was a pragmatist who saw control, not debate, as the key to stability. From the outset, Lee set about welding together four distinct ethnic groups—Chinese, Malay, Indian, and others—into a cohesive national identity. To him, society was not a platform for representation but a mechanism for coordination.

The objective was not representation. It was legibility. From inception, Lee conceived of Singapore as a controlled interface: rule-of-law for capital, rule-by-law for citizens. Parliamentary process was retained as theatre; real authority was routed through the executive. The press was not free—it was functional. Government-linked media ensured signal continuity. Dissent was not banned outright. It was procedurally filtered—opposition figures bankrupted, detained, or disqualified through targeted litigation. Liberalism was simulated, not practiced.

Lee’s program was not ideological—it was diagnostic. Social fragmentation was not addressed by consensus-building but by formatting. Postcolonial identity was treated as a liability. The Japanese occupation still loomed large—fresh in memory, brutal in consequence. It had shown what disorder permitted: executions, rape, forced labour. Lee’s response was pre-emptive containment. Behavioural engineering replaced political debate. The Housing Development Board (HDB) recoded the city: multi-ethnic quotas, spatial redistribution, and vertical integration of community. The HDB was not merely an engineering marvel—it was a civics firewall. Urban planning replaced political organising. Streets were safe because previous rub-points were dissolved. Through the Ethnic Integration Policy, demographic balance was enforced not through dialogue, but through architectural quotas.

This was not repression by Maoist trauma. It was control by civilisational prosthetics. No struggle sessions. Just clean pavements and mandated obedience. The public was taught to fear chaos, not power. Meritocracy became the new ritual. The national elite were not elected—they were compiled through elite education: filtered through Anglo-American legal frameworks, econometric training, and engineering doctrine. Politics was deprecated. Policy became throughput. Elections were retained as interface validation—performance legitimacy in simulation mode.

Lee’s technocratic authoritarianism became elite training—not just for Singaporeans, but for those observing abroad. Western universities partnered with Singaporean institutions. Harvard, LSE, Stanford all admired the yield curve. World Bank reports praised the efficiency. Transparency International overlooked the suppression. What mattered was output. And output came. Low crime. High literacy. Trade surplus. Safe streets. The authoritarian shell was masked in cosmopolitan skin. Clean, legible, and performant.

Singapore presented a different inheritance. Where Hong Kong was the commercial detritus of British laissez-faire—chaotic, stratified, and partially governed—Singapore was engineered from inception. At independence, it had no natural resources, no rural hinterland, and no room for entropy. Lee Kuan Yew imposed order not as correction, but as precondition. Behaviour was reformatted, housing standardised, speech bounded. It was not liberalism. It was compression.

In contrast, Hong Kong—also a British possession until 1997—remained unresolved. A volatile fusion of extreme wealth and social precariousness, it housed thousands in subdivided flats and cage homes while hosting one of the world’s most aggressive financial sectors. Gambling dens, informal markets, and colonial nostalgia coexisted under a rule-of-law regime designed for trade, not justice. Governance was transactional. Legibility was optional.

Singapore became a proof-of-concept: an admissible prototype for technocratic governance with minimal friction. This was not a smaller China. It was China’s mask posing as China’s antithesis—a sanitised preview of Hong Kong’s reintegration and the emergent megacities of the mainland. Where China initially focused on the infrastructure of discipline—factories, cadres, surveillance nodes—Singapore built the user interface: legibility, efficiency, trust in throughput. One repressed in bulk. The other filtered in real time. Both delivered order by collapsing choice.

In structural terms, both China and Singapore operate on secularised variants of the Mandate of Heaven—reframed through performance, not proclamation. Authority does not arise from popular sovereignty, but from order, prosperity, and continuity. Collapse delegitimises. Competence sanctifies. This is the Mandate stripped of mysticism and recoded as throughput validator: the ruler rules because the machine runs. In China, this logic was formalised as the Dictatorship of the People—a contradiction that is not merely Leninist, but also culturally reframed. Here, “the people” are not a constituency but a test. Collapse invalidates rule. Prosperity confirms it. The CPC does not govern because it is chosen, but because it claims to embody the people—structurally, permanently, and without contest. Legitimacy is not conferred. It is assumed—validated post hoc by the absence of collapse.

Singapore internalised the same logic at micro scale: a single-party technocracy that justified itself through results. Elections became procedural acknowledgements of performance, not mechanisms of choice. In both cases, the governing class is sanctified by success. This structure has its analogue in the West, where noocracy—the rule of the cognitively credentialed—is emerging under the banners of expert governance, evidence-based policy, and algorithmic optimisation. The Dark Enlightenment makes this explicit: elite filtration over democratic input, stability over participation, legibility over pluralism. Across regimes, the convergence is clear. Legibility becomes legitimacy. Optimisation becomes authority. The Mandate persists. It has simply migrated formats—without restoring exits.

In Singapore, the system’s full-stack control logic surfaced unmistakably during COVID-19. Singapore enacted some of the most stringent containment protocols globally: digital contact tracing via the TraceTogether app and token, strict quarantine enforcement, wage surveillance, population segmentation by vaccination status. Singapore achieved one of the highest COVID-19 vaccination rates globally so that by late 2021, over 90% of the eligible population (aged 12 and above) had completed the full primary vaccination series. By early 2022, booster uptake also surged, with over 70% of adults receiving their third dose. The state framed vaccination not as a choice, but as a civic duty aligned with national interest—consistent with Singapore’s model of technocratic legitimacy through disciplined compliance. Push back was minimal. Public health became the pretext, but the circuitry predated the pathogen.

But this path to technocratic order has not been without cost. Lee’s design was not to replicate sovereignty—it was to simulate coherence. Beneath the sheen of efficiency, Singapore embedded a structural rigidity now surfacing as systemic risk. The very instruments that delivered cohesion—population control, elite filtration, managed dissent—also sterilised the polity. Fertility rates have collapsed, with marriage being delayed or abandoned. Work became sacrament, reproduction deferred. With a Total Fertility Rate of 0.97 in 2024, Singapore now faces a demographic cliff—accelerated by rising costs, deferred kinship, and a culture of optimisation that deprioritises family formation. Immigration may buffer the numbers, but it cannot reinstantiate the mindset that made the model coherent. Demography is not just numbers. It’s runtime. The polity’s mindset—deferred reproduction, algorithmic optimisation—cannot be reimported. It must be rewritten. And no state has yet found the compiler.

Nevertheless, the lessons of Singapore had already been extracted—its model reframed as a scalable blueprint for managing small, legible populations through elite stewardship, filtered participation, and infrastructural obedience.

Conclusion: Prototype, Protocol, Proof

The USSR, China, and Singapore form a triadic arc in the evolution of post-liberal governance. Each enacted a variant of control logic—Soviet command, Chinese refinement, Singaporean filtration. What the USSR tested through brute protocol, China scaled through infrastructural modulation. What China embedded in mass systems, Singapore demonstrated in micromodel clarity.

In China and Singapore, the Mandate persists as secular providence. In the West, noocracy disavows mysticism—but reasserts destiny as algorithm. None of these models arises from popular mandate. All are engineered in the aftermath of collapse—imperial, civilisational, or colonial. And each produces legibility at scale: managed populations, standardised behaviours, loyalty without participation. Dissent is not crushed uniformly. It is pre-empted, reformatted, or rendered structurally irrelevant.

Resistance persists in differentiated vectors: GDPR’s biometric constraints, WHO’s genomic IP disputes, Indigenous data sovereignty, and biohacker subversion. These are not counter-systems. They are structural interferences—evidence that the protocol is active, but not yet total. Iceland’s opt-in model remains anomalous. Its viability depends on demographic scale, public trust, and constitutional oversight—conditions incompatible with global data liquidity. Opt-in governance halts the flow. That’s why no major platform has adopted it.

Together these cases map a convergence trajectory—away from ideology, toward function; away from representation, toward throughput. What began as revolutionary dogma becomes recursive optimisation. As governance converges on optimisation, the political disappears—not through repression, but through redundancy. Governance ceases to be a contest of visions. It becomes a calibration of signals.

I watched part of this arc unfold. As a teenager in Singapore in the early 1970s, without recognising it at the time, I saw the liberal inheritance disassemble itself in real time. The detentions weren’t denied—they were applauded. Cleanliness wasn’t hygiene—it was compliance protocol. Spitting fines weren’t symbolic—they were disciplinary code. At the time, it felt like order. In retrospect, it was scaffolding. Lee Kuan Yew didn’t obscure the reprogramming—he announced it—and much of the population affirmed it. The operating system was already compiling.

The Cold War frame still loomed—Vietnam’s collapse, the Malaysian Emergency, the domino theory. But this was never about communism. Nor capitalism. Nor West versus East. It was about command logic—encoded, tested, refined, exported.

The next stage is global. But that is for the next article, Part 7. The Export Layer — Runtime Governance Goes Global

Acknowledgements

This analysis intersects with Nick Land’s The Dark Enlightenment (2012) in its treatment of anti-democratic trajectories, and with Patrick Wood’s Technocracy Rising (2015), which documents technocracy as systemic drift rather than policy choice. Frames and concepts from Land, Yarvin, and Thiel are referenced across the Overlords series as diagnostic tools, repurposed to expose the structural logic, custodianship and continuity of the system—in no way should this be constructed as evidence of my support or advocacy for their positions.

Published via Journeys by the Styx.

Overlords: Mapping the operators of reality and rule.

—

Author’s Note

Produced using the Geopolitika analysis system—an integrated framework for structural interrogation, elite systems mapping, and narrative deconstruction.