Overlords Part 9: The Oligarchic Class – Fabricated Wealth, Conditional Power

How capital anchors serve empire: the tethered autonomy of the billionaire class.

The Operating Class, mapped in Part 8, manages the runtime of empire—technocrats, bureaucrats, advisers, and think tankers. Their function is execution. Beyond them sits the oligarchic class. These are not operators but owners: families, moguls, dynasts, asset managers. Their names recur in Forbes’ rankings of the richest 10, 20, or 100 individuals, paraded as symbols of merit, genius, and entrepreneurial achievement. They form the Oligarchic Class.

Yet ownership is misleading. The inclusion of figures like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Bernard Arnault, and Mukesh Ambani illustrates the point. Musk is cast as a singular innovator, but his empire rests on state contracts and regulatory scaffolding. Bezos is presented as a retail visionary, though Amazon’s rise was underwritten by Pentagon and CIA contracts. Arnault appears as the French captain of luxury, yet functions as custodian of cultural capital that fuses European soft power with global consumer markets. Ambani represents “emerging market” dynamism, but Reliance Industries is inseparable from India’s state concessions and protectionist industrial policy.

Forbes frames these names as personal triumphs of enterprise. In reality, each exemplifies curation. Their wealth anchors capital into the system, but their autonomy is conditional. They are admitted, disciplined, recycled, and constrained. The proper image is not a ladder of merit or a pantheon of genius entrepreneurs, but a concentric ring of tethered asset nodes—each connected by wealth but orbiting the system, never apart from it. They ballast the architecture with capital, and in doing so, remain bound by it. As with the case studies provided in Part 8’s Addendum 2, Addendum 3 carries the case studies related to this article—a selection individual oligarchs rendered as structural examples.

Wealth as Axis, Not Endpoint

Wealth is not sovereignty. It is the axis around which oligarchs revolve, but it does not confer authority by itself. Possession of billions—paraded in Forbes tables—secures visibility but not command. In systemic terms, wealth functions as conditional entry: leverage sufficient to justify admission into elite networks, not license to dictate outcomes. The oligarchic class holds ballast, not sovereignty.

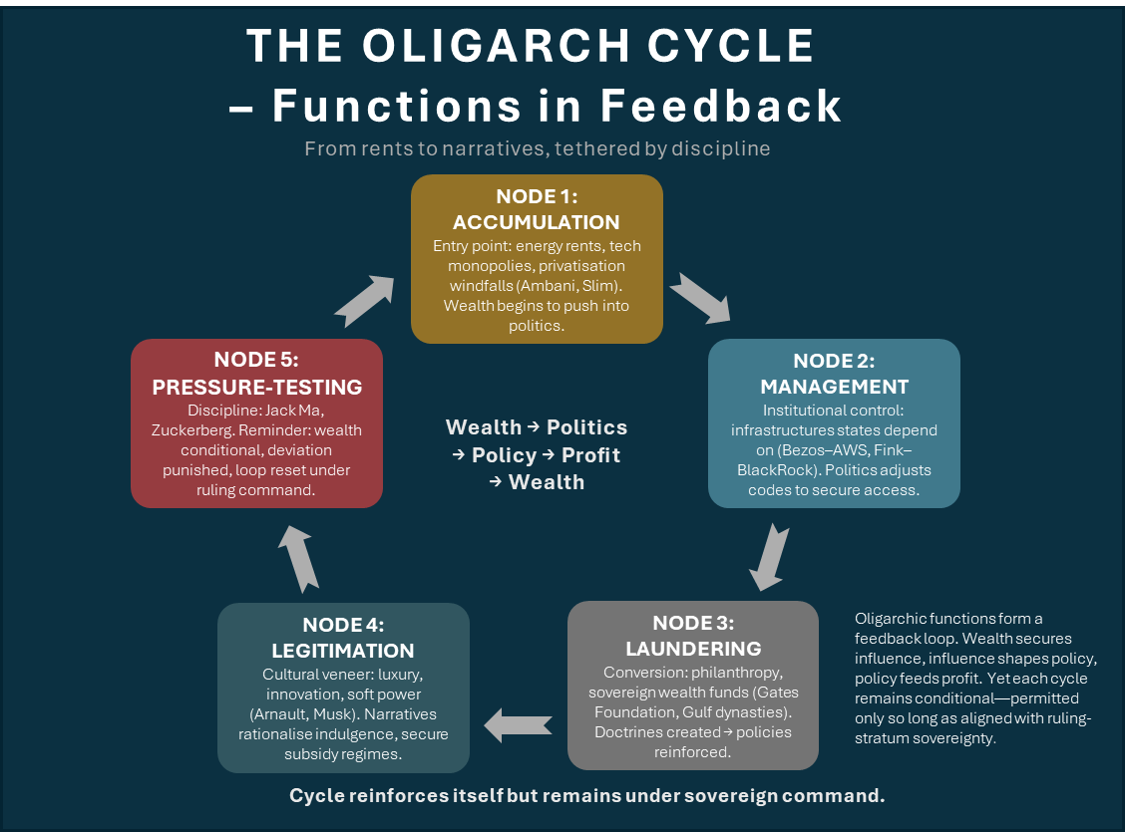

Their functions operate in sequence but also in loop, creating a self-reinforcing cycle.

Accumulation is the entry point. Energy rents, platform monopolies, or privatisation windfalls create fortunes—Ambani in India, Slim in Mexico—but these fortunes become politically salient only when positioned to fund parties, lobbyists, and media channels. The wealth itself pushes against the political membrane.

Management institutionalises this pressure. Bezos through AWS, Fink through BlackRock—they do not just hold money, they control infrastructures on which states depend. Political actors, in turn, adjust regulatory codes, procurement contracts, and subsidy streams to secure continued access.

Laundering converts extraction into acceptable form. Gates through the Foundation or Gulf dynasties through sovereign wealth funds: their spending creates think tanks, university chairs, and global initiatives that influence doctrine. These doctrines then shape policy landscapes—from health regulations to trade treaties—feeding back into the profit base that sustains the donor.

Legitimation makes the cycle visible as culture. Arnault’s luxury empire converts European heritage into global aspiration, underwriting diplomatic soft power that secures trade routes and tax regimes. Musk’s “innovation” brand rationalises subsidy regimes in aerospace and energy. Narrative glamour feeds regulatory indulgence, which secures profit.

Pressure-testing demonstrates boundaries but also resets the loop. Jack Ma’s fall warned Chinese entrepreneurs that wealth must feed Party priorities or be curtailed. Zuckerberg’s hearings in the US performed the same reminder: platforms may fund lobbying, but they cannot breach national security prerogatives. In both cases, discipline ensures the loop remains tethered—the money feeds politics, but politics is never sovereign; it is itself under ruling-stratum command.

The cycle is therefore recursive. Oligarchic wealth funds influence, influence scripts policy, policy secures rents, rents enlarge wealth. Yet above this circuit sits the Ruling Stratum. They determine admission, toleration, and exile. The oligarchs’ feedback loop is powerful but never autonomous: it is permitted only because it stabilises the architecture rather than threatens it.

Anatomy of Fabrication – Typology

Oligarchs do not emerge from a neutral marketplace of competition. They are fabricated—shaped through state concessions, regulatory umbrellas, dynastic inheritances, and ideological scaffolding. Their differences are less about personality than about the mechanisms of formatting. Four subtypes illustrate the schema.

a. Constructed Oligarchs (Permitted / Fronts)

Constructed oligarchs are the most visible—the “self-made” billionaires paraded as innovators—yet their ascents were scaffolded through state concessions, legal shields, and security patronage. Jeff Bezos is cast as retail genius, but Amazon’s decisive leverage came from Amazon Web Services, secured through Pentagon and CIA contracts. The company functions as government infrastructure under private branding. Mark Zuckerberg, the dorm-room myth, scaled Facebook behind Section 230 liability immunity and intelligence-linked venture capital; his “move fast and break things” ethos depended less on invention than on regulatory indulgence. Larry Ellison’s Oracle grew directly out of a CIA-funded database project, embedding his firm in military and intelligence procurement. Alex Karp’s Palantir follows the same model—capitalised by In-Q-Tel, sustained by Pentagon and intelligence budgets, marketed as private innovation while in reality a state contractor.

The Russian oligarchs of the 1990s provide the rawest demonstration. Minted by IMF-designed shock therapy and Western banks, they became billionaires overnight, only to be later recaptured and reformatted by Putin as “service oligarchs” bound to state direction.

The function here is proxy service. These figures appear as national mascots or entrepreneurial archetypes, but their wealth is conditional on remaining inside the frame. The cycle is predictable: accumulation under legal and fiscal shields; lobbying to entrench those protections; regulation to secure monopoly. At every stage, the state is the silent partner. Constructed oligarchs are front-end actors for deeper strategies—the spectacle of prosperity masking the machinery that engineered them.

b. Opportunistic Oligarchs (Absorbed / Integrated)

Opportunistic oligarchs originate not from deliberate state design but from contingency—crisis moments, weak governance, or post-colonial restructuring. Mining magnates, landholding dynasties, and telecom barons emerge when rents are left exposed. Yet their longevity depends on integration into higher circuits. Without tethering to donor regimes, global banks, or imperial sponsors, they remain fragile.

African extractive elites illustrate this dynamic. Fortunes from cobalt, oil, or gold are viable only if channelled through World Bank- or IMF-sanctioned frameworks. Contracts are underwritten by multilateral finance, and profits circulate through London, Geneva, or Dubai. Disconnection risks sudden irrelevance—or replacement. Similarly, Latin American agrarian and industrial families survive only when folded into the US umbrella. Landed wealth in Brazil or Mexico persists because it is entwined with trade deals, security agreements, or regional financial circuits.

Opportunistic oligarchs emerge through rupture—liberalisation shocks, currency crises, or external sponsorships. They lack dynastic ballast or constructed branding, relying instead on seizing transitional openings. Carlos Slim’s Mexican telecom empire, or Aliko Dangote’s cement and commodities networks, illustrate fortunes grown from regulatory collapse and political patronage rather than entrepreneurial innovation. Their wealth finances domestic political parties, media, and patronage systems, but their survival requires continued sanction from imperial capital and political cover. If they overstep—by seeking autonomy from these frameworks—they are swiftly curtailed.

In this sense, opportunistic oligarchs are buffers. They provide local ballast to global extraction, absorbing social tension while funnelling legitimacy upward. Their fortunes look like opportunism, but their endurance shows absorption: they must submit to the loop, feeding political influence domestically, aligning with donor or sponsor agendas internationally, and returning wealth back into accumulation. They are less spectacle than Constructed oligarchs, but equally conditional.

c. Dynastic / Migratory Oligarchs (Hinge)

Every oligarchic formation has a starting point. The oldest of the contemporary dynastic lineages are the Rothschilds—emerging in the late 18th century, rising through the 19th as financiers of wars, states, and sovereign debt. Their position was never merely accumulation of private wealth but direct tethering to rulers: monarchs and empires borrowed through Rothschild houses, embedding the family not simply in markets but in the architecture of sovereignty itself. For more than 250 years they have financed states and crowned heads, their name shorthand for oligarchic embeddedness.

The Rockefellers followed a century later, in the late 1800s, through Standard Oil. Unlike the Rothschilds, their foundation was industrial rather than financial. But as Standard was broken and capital restructured, the Rockefeller fortune migrated into banks, endowments, and foundations. Their philanthropy became ballast for institutions—the University of Chicago, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Council on Foreign Relations—reformatting oil wealth into systemic influence. Over time, Rockefeller philanthropy did not merely fund science or social reform, it underwrote frameworks of governance. The Club of Rome, launched in 1968 with Rockefeller sponsorship, illustrates this pivot. Its “Limits to Growth” report (1972) popularised resource scarcity and ecological crisis narratives, but these functioned as wealth-protection mechanisms. The green agenda became a disciplinary apparatus—justifying technocratic management of energy and population under the language of planetary stewardship. Ecological scarcity reframed Rockefeller capital not as liability but as arbiter of survival.

Crucially, there are indications of intermarriage and alignment between Rockefeller and Rothschild lines, a convergence that elevated both: the Rockefellers migrated from industrial barons into the same echelon of transnational finance, while the Rothschilds extended their embeddedness into American capital. Through shared foundations, joint ventures, and policy networks such as the Club of Rome, their fortunes fused into a dual axis—finance and industry reformatted as governance itself.

Other dynasties—the Agnellis in Italy, with Fiat wealth consolidated into investment holdings—follow the same pattern on a narrower scale. What begins as industrial or national fortune migrates into global portfolios, family offices, banks, and foundations.

Modern figures like George Soros or Larry Fink (BlackRock) function in continuity with this lineage. They may not carry centuries of family history, but they manage capital at such scale—hedge funds, index funds, sovereign wealth interlocks—that they shape the very rulesets states must follow. Fink’s BlackRock, with trillions under management, is now an infrastructural actor for governments and central banks. Soros’ Open Society network has influenced political frameworks across continents.

The function of dynastic and migratory oligarchs is hinge-work. They do not merely accumulate; they connect. Their position is between operators (Part 8) and rulers (Part 10), ensuring that oligarchic wealth is tethered to sovereign command. They script frameworks through asset allocation, endowment design, and philanthropic capture. They are ballast managers: the Rothschilds financing kings, the Rockefellers underwriting think tanks, Soros funding transitions, Fink disciplining entire markets.

They are less visible as innovators, more permanent as custodians. Their significance lies in continuity—migration of wealth across generations, interweaving of dynasties, and consolidation of fortunes into the mechanisms by which capital itself rules.

d. Hybrid Oligarchs (Masks of Governance)

Hybrid oligarchs fuse entrepreneurial performance with systemic dependence. Bill Gates became the archetype: Microsoft’s early ascendancy was underwritten by state contracts and legal insulation, later reframed through philanthropy as benevolent stewardship. Elon Musk plays a similar role—SpaceX and Tesla exist only through procurement and subsidy, yet the narrative casts him as lone innovator. Jack Ma’s arc completes the pattern: once permitted to embody Chinese market dynamism, he was curtailed the moment the mask slipped against Party priorities.

Bill Gates exemplifies this trajectory. The founding act of Microsoft was not invention but acquisition. In 1980, Gates secured rights to QDOS (“Quick and Dirty Operating System”), a program written by Tim Paterson at Seattle Computer Products. Rebranded as MS-DOS, it was licensed to IBM for its first personal computer. Crucially, Microsoft retained the right to license the software independently, ensuring its dominance across the exploding PC market. Gates’ fortune thus rested on an opportunistic purchase and a strategic licensing arrangement, not on technological originality. State–corporate scaffolding—IBM’s procurement decision, antitrust indulgence, intellectual-property shields—ensured Microsoft’s rise. Gates’ later turn to philanthropy laundered monopoly rents into global legitimacy. Through the Gates Foundation, his money shaped health, education, and agriculture policy across continents—governance disguised as altruism. The “benefactor” mask obscures the reality of extractive origins and institutional capture.

Elon Musk plays a parallel role as performer of innovation. Tesla’s technology was built by engineers Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning; Musk entered as investor, then displaced them. SpaceX builds on decades of NASA and Air Force R&D, sustained by state contracts and subsidies. Neuralink draws from longstanding neuroscience research. Musk did not invent these fields; he branded and dramatised them. Downward, toward publics, he performs the lone visionary. Upward, toward the state, he legitimises subsidy and industrial policy as market triumph. His mask is progress theatre—converting dependency into inspiration.

Jack Ma illustrates the limits of the mask. Presented as the miracle entrepreneur of China’s market opening, he functioned as a symbol of national prosperity until his ambitions collided with sovereign financial controls. When his independence threatened the Party’s command over credit and payments, he was disciplined—his mask tolerated only while aligned with state legitimacy.

The function of hybrid oligarchs is ideological laundering. Gates performs benevolence, Musk performs genius, Ma performs miracle. Each converts state concessions, subsidies, and contracts into cultural narratives of progress. The loop is consistent: money generates influence, influence scripts policy, policy restores wealth, and the mogul’s image makes the cycle palatable. The mask is not accidental—it is the very function.

Pathways – Origin, Integration, Function

Oligarchic formation is not accidental. It follows structured pathways where fortunes are scaffolded, absorbed, and repurposed. Origins vary, but integration converges, and functions remain predictable.

Origins take four main forms. Some emerge through state concessions—energy rents in the Gulf, or Russian assets stripped under IMF shock therapy. Others are sheltered by tech umbrellas, where liability shields and subsidy enable scaling—Facebook under Section 230, Amazon through US defence procurement. Dynastic inheritance supplies ballast, as with Rothschild finance or Rockefeller oil. And in one of the most egregious cases, pharmaceutical monopolies were built through state protection: public research and taxpayer-funded trials handed over to private firms who then locked in patent regimes. Big Pharma fortunes rest on government R&D pipelines, indemnity against liability, and procurement contracts that guarantee profit regardless of outcome. Few oligarchic empires illustrate the fabrication process more starkly.

Integration is the filtering stage. Wealth is not sufficient for endurance; it must be tethered to elite networks, pooled into transnational finance, or aligned with sovereign strategies. African mining barons survive only when ratified by donor institutions; US moguls only when supplying government infrastructure; dynasts only when underwriting imperial policy forums. Big Pharma’s integration is exemplary: it sits astride state health systems, the WHO, and philanthropic foundations, ensuring its rents are locked in at the global scale.

Functions are fixed. Oligarchs operate as extractive nodes (resource rents, data monopolies, pharmaceutical cartels), legitimisers (philanthropy, cultural sponsorships), symbols (entrepreneurial masks), or managers (custodians of capital pools). These roles cycle, but the pattern does not change.

The mythology frames them as society’s great benefactors. Structurally, they are its greatest beneficiaries—their empires built on subsidies, contracts, liability shields, and public underwriting. Big Pharma is perhaps the purest case: public money funds the science, states absorb the risks, and corporations extract monopoly rents—then launder them through “global health” philanthropy. Philanthropy is not repayment but cover: recycling extracted wealth into legitimacy while protecting the flows that sustain it. Addendum 3 sketches a selection of these figures in detail, but the point here is circulatory. Oligarchs do not invent or bestow; they are fed, processed, and redeployed.

Conditional Power – Boundaries of Oligarchy

Oligarchic power is conditional. Permission is always revocable. The oligarch operates on licence, not sovereignty. Their fortunes may be vast, but the terms of survival are tethered to alignment with the schema. Wealth is tolerated only insofar as it remains inside the frame.

The disciplining of Jack Ma is emblematic. Once the face of China’s private-sector “miracle,” he was erased from view after criticising regulators in 2020. His Ant Group IPO was halted, Alibaba was restructured, and Ma himself reduced to occasional, tightly managed appearances. The principle was unambiguous: capital does not override Party command.

In Russia, the 1990s oligarchs were minted by IMF shock therapy, then corralled by Putin. Boris Berezovsky, once a kingmaker, fell into exile and died in suspicious circumstances in London. Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Russia’s richest man through Yukos, was imprisoned and stripped of assets after overstepping into politics. Even Roman Abramovich, long tolerated as a service oligarch, saw his assets frozen and his position in London dismantled when geopolitical alignment shifted.

Ukraine follows the same pattern. Ihor Kolomoisky, whose media empire and financing propelled Volodymyr Zelensky to power, was later sanctioned, stripped of citizenship, and arrested on fraud charges once his presence became incompatible with Western frameworks. The lesson is structural: oligarchs may create presidents, but they cannot outlast the schema that tolerates them.

In the West, discipline operates through ritualised spectacle rather than open seizure. Mark Zuckerberg remains fabulously wealthy, yet his periodic congressional hearings function as reminders—antitrust threats and privacy probes staging his dependence on political indulgence. Elon Musk illustrates the same leash. Once a Trump ally, he ran DOGE (Department of Government Efficiency) and backed Republican reforms, before denouncing Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill” as a “disgusting abomination” and threatening primary challenges. His flirtation with a third party was public but ultimately performative. Procurement contracts, subsidies, and regulatory indulgence remained the true levers of discipline. Even as he postures as maverick, the architecture holds him inside.

This is the boundary of oligarchy. They ballast the system with capital and spectacle, but they do not command it. Their legitimacy is provisional, their fortunes reversible, their status conditional. The moment they transgress or endanger the architecture, the leash is tightened. Figures like Ma, Zuckerberg, Musk, Abramovich, Kolomoisky are paraded as titans yet remain proxies, their wealth licensed and always recallable.

By contrast, the Rothschilds and Rockefellers are never disciplined in this fashion. Their wealth has long since been institutionalised—embedded in banks, endowments, and foundations—indistinguishable from the very architecture of governance and finance. Here oligarchy shades into the Ruling Stratum.

Together they form the oligarchic ring: tethered nodes of capital that orbit the system, never sovereign, always bound.

The Oligarchic Ring – Structural Imagery

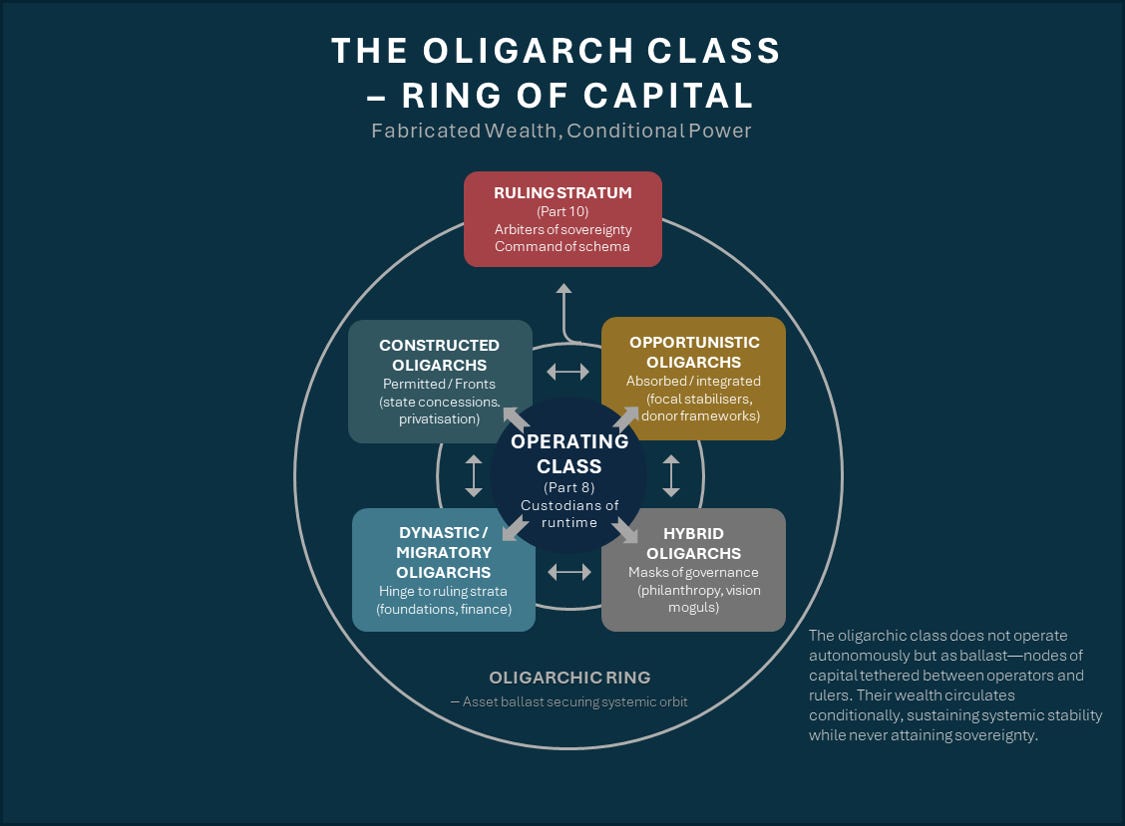

The system is concentric, not linear. The Operating Class (Part 8) sits at the core, managing runtime: technocrats, bureaucrats, advisers, and think tankers. Around them is arrayed the oligarchic ring: nodes of capital tethered to the schema, their wealth acting as ballast. Beyond, in the outermost orbit, stands the Ruling Stratum—arbiters of sovereignty whose authority is not conditional but constitutive.

The oligarchic ring must be understood as functional architecture. Each node—Bezos, Musk, Abramovich, Gates, Rothschild, Rockefeller—appears as an individual fortune, but structurally they are anchors. Their capital is not private autonomy but systemic weight, stabilising flows of finance, technology, energy, and ideology. Some are conditional mascots, vulnerable to recall or humiliation; others are dynastic dynamos, whose wealth has become indistinguishable from governance itself.

The imagery is planetary: operators form the dense inner core, oligarchs the ring system binding and stabilising, and rulers the gravitational axis. The ring is indispensable but not sovereign. Oligarchs orbit; rulers command.

It is this architecture that will carry forward into Part 10, where the Ruling Stratum—the sovereign echelon beyond conditional wealth—is anatomised.

Closing Vector – From Oligarchs to Sovereigns

The oligarchic class anchors but does not command. They stabilise the system through capital, but sovereignty rests elsewhere—with the Ruling Stratum who set boundaries, admit or exile, legitimise or erase. The myth of the sovereign billionaire collapses here. Oligarchs may front as visionaries, benefactors, or dynasts, but they remain instruments of systemic logic.

The next step is Part 10: The Ruling Class, where sovereignty is defined, and oligarchs—however wealthy—must bend. But if even billionaires are bound, what kind of power operates without leash, without proxy—only command?

Acknowledgements

This analysis echoes Peter Thiel’s “The Education of a Libertarian” (2009) and “Competition Is for Losers” (Wall Street Journal, 2014), which critique fabricated wealth and emphasise the distinction between financialised illusion and sovereign technological command. Frames and concepts from Land, Yarvin, and Thiel are referenced across the Overlords series as diagnostic tools, repurposed to expose the structural logic, custodianship and continuity of the system—in no way should this be constructed as evidence of my support or advocacy for their positions.

Published via Journeys by the Styx.

Overlords: Mapping the operators of reality and rule.

—

Author’s Note

Produced using the Geopolitika analysis system—an integrated framework for structural interrogation, elite systems mapping, and narrative deconstruction.