Overlords: Part 8. The Operating Class – Not Elected, Not Elite, But Everywhere

The embedded custodians of global governance—trained to enforce the code, not question it.

Across the Overlords series, the same system has appeared in changing masks—politics staged as performance, governance executed as protocol, consent reduced to a conditional gate. The early chapters followed its substitution of representation with stacked compliance mechanisms, its elevation of soft law above constitutional limits, and its binding of identity frameworks to biological pass-keys. Part 1 exposed electoral theatre as scripted compliance. Part 2 mapped the layered logic of behavioural enforcement. Part 3 detailed soft law's override of sovereignty. Part 4 tracked the conversion of identity into access. Part 5 revealed the genetic gating of the human subject. Part 6 shifted focus from static architecture to live trials, showing how distinct regimes acted as laboratories for control. Part 7 explored how runtime governance has gone global.

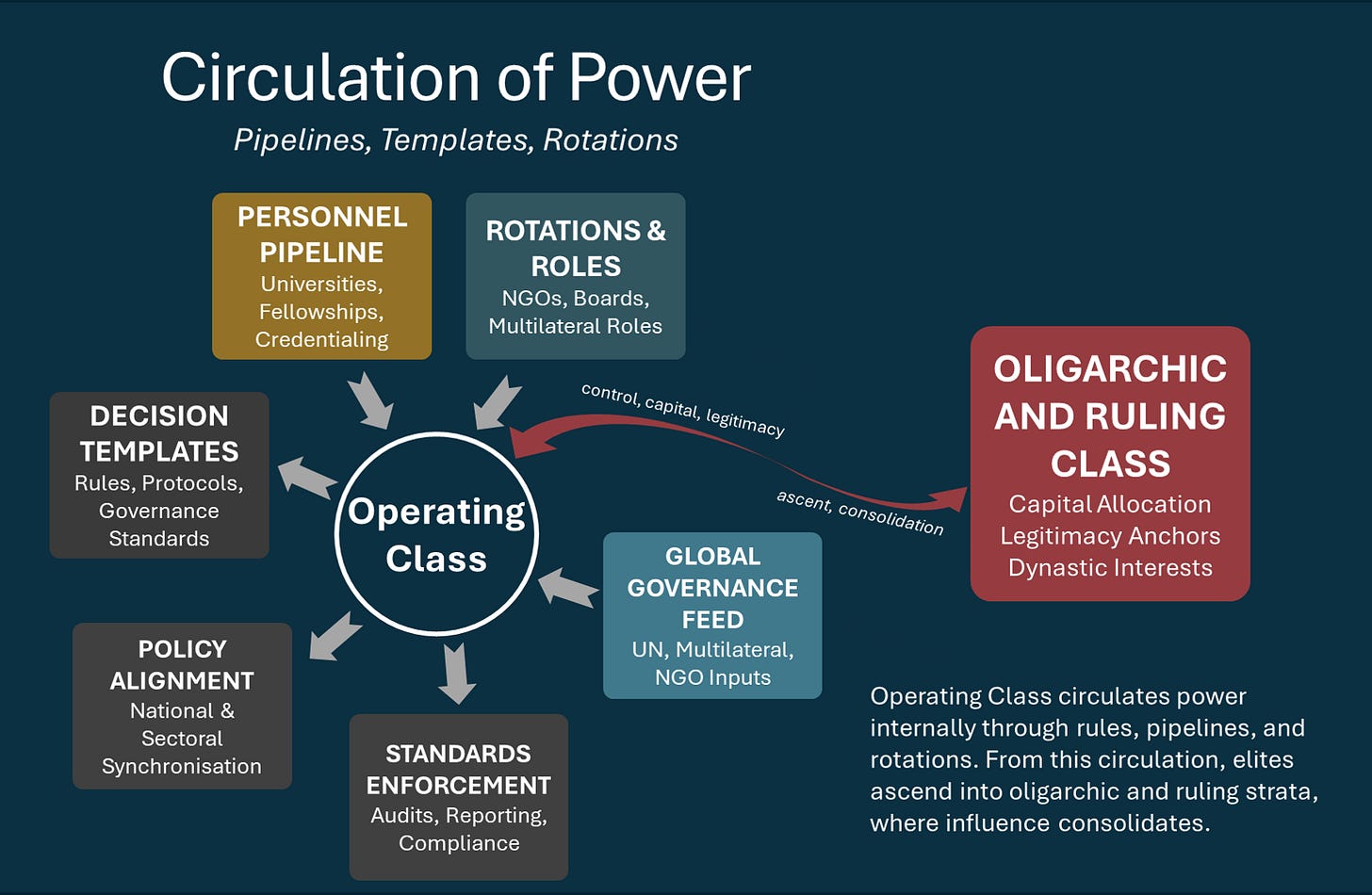

Part 8 follows the shift from architecture to operators. Where Part 7 mapped the harmonisation engine as the institutional layer synchronising finance, health, surveillance, and sustainability, this instalment turns to the people who keep that engine running. Not elites in the hereditary sense, nor elected in the democratic sense, but an Operating Class—a permanent managerial stratum—trained, credentialed, and embedded across jurisdictions, acting as the interface between global consensus and local enforcement. A selection of specific case studies of eight these operators—some well-known and others more in the shadows—is set out in Addendum 2, allowing this main chapter to focus on their functions, recruitment pipelines, and systemic role.

Introduction – Defining the Operating Class

The Operating Class occupies a layer of governance that is neither visible to the public nor bound by the formal cycles of political change. They are distinct from hereditary elites, whose influence rests on legacy wealth and title, and from elected officials, whose authority is conditional on periodic endorsement. Their role is not to own the system or to win the next vote, but to keep the system running—irrespective of which flag is flying above it.

Part 7 identified the harmonisation engine as the institutional mechanism through which health, finance, surveillance, and sustainability are brought under a single administrative runtime. The Operating Class is the human interface for that engine. They move between ministries, corporate boards, multilateral agencies, and “non-governmental” governance bodies, carrying the same rule-sets into each. In one posting they may be a regulator, in the next a foundation chair, in the next a special envoy. The organisational nameplates change, but the function persists: translate the consensus forged in elite policy circles into binding operational practice on the ground.

This stratum has been partially mapped before. Peter Phillips’ Giants: The Global Power Elite followed the global power elite through corporate board interlocks, showing how institutional control was consolidated without public recognition. Archival-based scholarship of Dino Knudsen (2016) describes the Trilateral Commission as a transnational coordination forum linking political, corporate, and academic actors, shaping policy consensus outside formal democratic channels. John Perkins’ Confessions of an Economic Hitman described the enforcement wing of this order—agents tasked with binding nations into its financial circuitry. John Coleman’s Committee of 300, while widely seen as conspiratorial in tone, offers one interpretive tradition for how policy networks can self-identify as transnational operators—but this is distinct from, and more speculative than, institutional histories grounded in works like Phillips or Knudsen. As establishment insiders like David Rothkopf (Superclass: The Global Power Elite and the World They Are Making) acknowledge, this transnational set moves seamlessly between public office, corporate boards, and policy bodies, carrying with them the same governance templates irrespective of nominal employer or jurisdiction. Each, in their way, illuminated segments of a network whose members survive changes in political weather because their legitimacy comes from credentialed access, not electoral mandate.

It is a mistake to view them as conspirators in the cinematic sense, coordinating in secret rooms to execute a unified master plan. Their power lies in a more durable structure: a transnational, credential-gated network where norms and protocols are set upstream of any democratic process, and where career progression depends on enforcing those protocols faithfully. They do not need to align on ideology—only on the non-negotiables of system maintenance.

Whether acting under the banner of national interest, corporate mission, or humanitarian obligation, the functional output is the same—alignment with harmonised protocols set beyond any single electorate’s reach

This part of the Overlords series examines that class as a systemic component. It maps their functions, their recruitment pipelines, and the environments in which they operate. The individual faces change, but the role is persistent: maintain the runtime, enforce the standard, and ensure the system survives the churn of politics.

Origins – From Technocrats to Custodians

The handover from politician-as-operator to technocrat-as-custodian did not occur in a single moment—it was the cumulative effect of institutional redesign, credential expansion, and network consolidation. In the post-war decades, electoral leaders still occupied the machinery of rule directly. Cabinets debated and directed policy; ministers owned the levers they pulled. But by the 1970s, policy execution was shifting into the hands of specialist administrators whose authority derived not from a vote count but from professional accreditation and inter-agency placement. The shift was rationalised as “modernising” government—streamlining decision-making, outsourcing complexity to those with technical mastery, and insulating critical functions from partisan turbulence. What it achieved was the relocation of operational control into a cadre that could outlast political cycles, and whose loyalty was not to a constituency but to the governance schema itself.

This transformation was not organic. It was engineered through the convergence of elite grooming platforms and policy synthesis hubs. Institutions like the Atlantic Council, the Trilateral Commission, and the World Economic Forum’s Young Global Leaders programme acted as recruitment filters and ideological aligners. Membership has never been purely Western—senior political, corporate, and administrative figures from Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America pass through the same induction circuits. Once inside, participants are rotated through multilateral boards—WHO committees, Gavi governance panels, World Bank consultancies—where they absorb the grammar of harmonised policy and the metrics by which compliance is measured. The result is a professional culture fluent in the enforcement of global protocols across borders and sectors, irrespective of regional origin.

While institutional mandates and national contexts differ, the structural logic binding these actors remains constant—protocol adherence as the condition of relevance—irrespective of internal disagreements or policy failures. The same operating templates appear in Beijing’s public health technocracy, Singapore’s smart city governance, and Gulf sovereign wealth strategy, though their operators are less visible in Western media ecosystems.

By the time the 21st century opened, the political class was increasingly decorative. Ministers and presidents became the public face of decisions already drafted, costed, and scheduled by the custodians. Whether under the cover of economic reform, humanitarian aid, or security doctrine, the substance of governance had migrated upstream into credentialed, networked hands—precisely the Operating Class whose function this article dissects.

System Functions – The Operating Class in Action

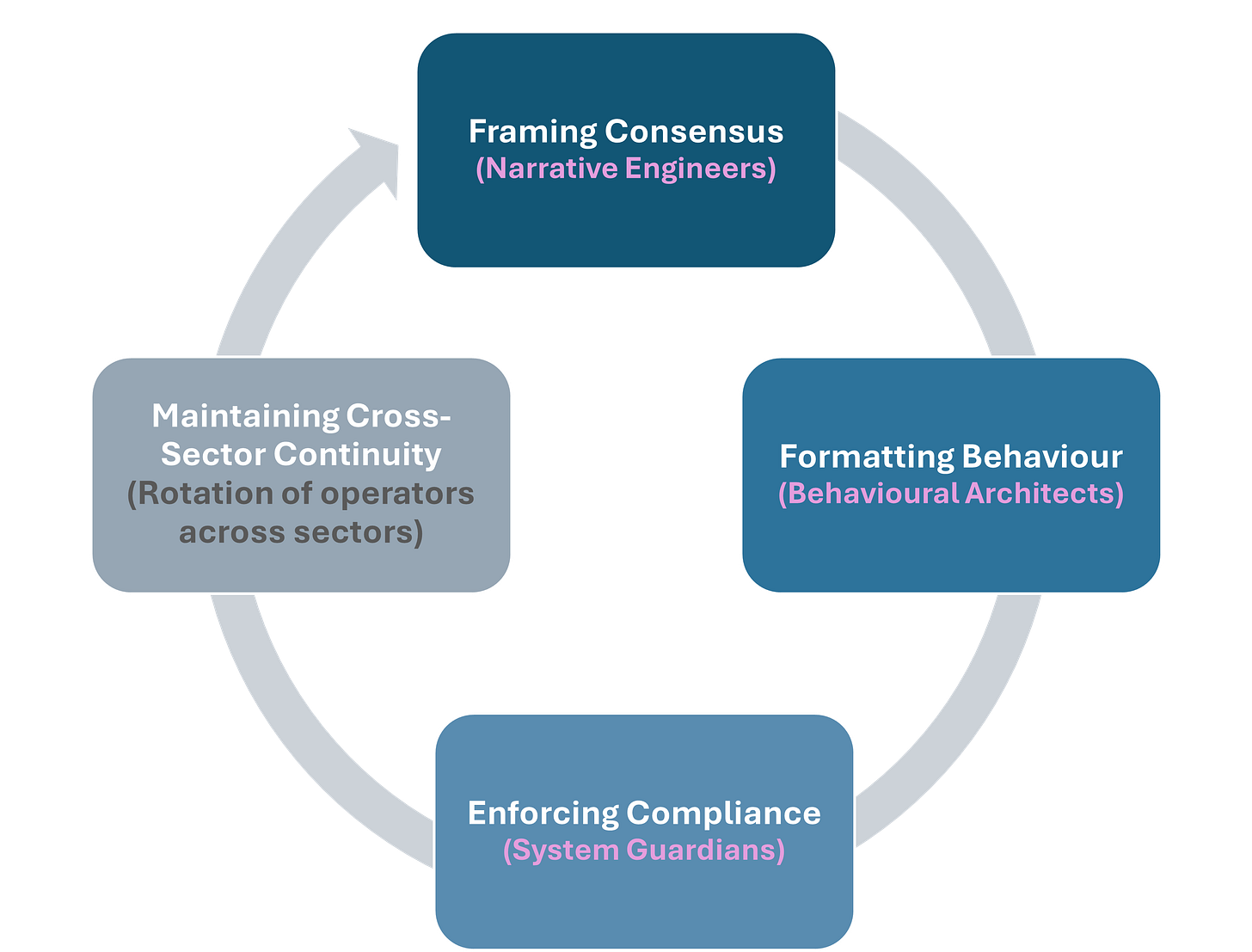

The Operating Class executes a continuous governance loop—translating elite consensus into enforceable reality, formatting populations for compliance, and ensuring system continuity across contexts. This loop can be broken into four core functions:

Framing Consensus – Elite agreements reached in Davos, Bretton Woods forums, or G7 ministerials do not enter public discourse unaltered. They are reframed by operators who make the logic palatable and defensible in national and sectoral contexts. This is the work done when Mark Carney presents climate finance as a market inevitability rather than an elite directive, or when Ursula von der Leyen describes digital identity infrastructure as “citizen convenience.” The aim is not to debate the decision—it is to limit the horizon of permissible narratives until the chosen frame is the only viable public position.

Formatting Behaviour – With the sanctioned frame established, operators embed it into environments that condition conduct. Jane Halton’s role in pandemic preparedness frameworks and simulation drills shows how behavioural defaults are engineered long before public health orders are issued. The UK’s Behavioural Insights Team, or Canada’s Public Health Agency during COVID, integrated health messaging with workplace rules, travel permissions, and consumer services so that compliance became the default and deviation carried rising friction.

Enforcing Compliance – Operators at this stage convert norms into obligations. Regulatory directives, ESG benchmarks, and sectoral licensing all act as enforcement arms. This is where a European Central Bank climate stress test, a UN global pandemic treaty clause, or a tech platform’s terms-of-service update become mechanisms for excluding non-compliant actors from markets, funding, or audiences. The enforcement layer operates with legal, financial, and reputational levers—often simultaneously.

Maintaining Cross-Sector Continuity – Once embedded, governance logic is preserved and redeployed through personnel rotation. Anthony Fauci can exit US federal service and immediately assume a role on a global health board, carrying the same pandemic governance architecture into a different institutional setting. Mark Carney’s shift from central banking to climate finance and then being slotted into the role of Canadian Prime Minister keeps much the same metrics and compliance models in play. By overlapping board seats, advisory roles, and fellowships, operators ensure that the system’s logic survives electoral cycles, public backlash, or sectoral crises.

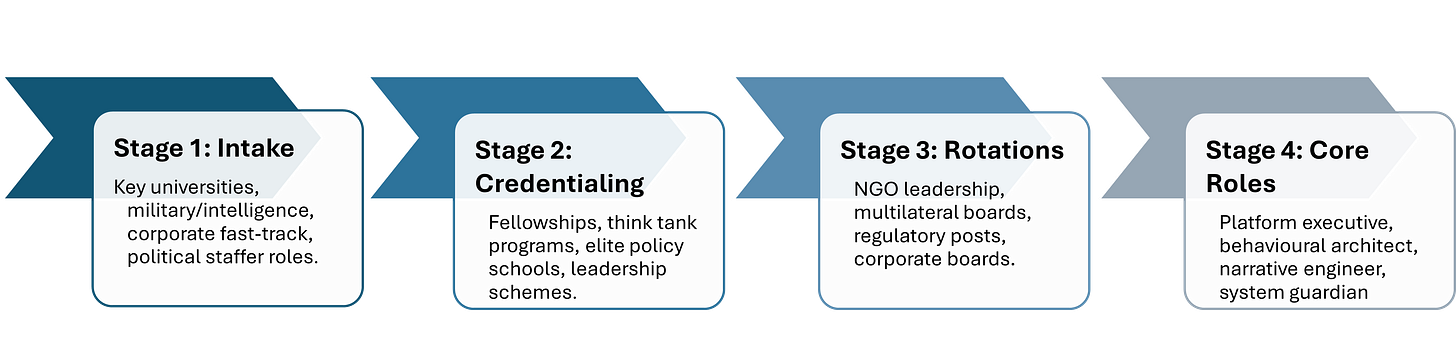

The same operators often cycle through all three functions—crafting the narrative in one role, designing compliance frameworks in another, and enforcing standards in a third—without ever leaving the system’s inner ring. Their careers follow a deliberate carousel: credentialed entry through elite universities or fellowships, grooming in consultancies or policy forums, placement in high-visibility governance or corporate roles, then rotation back through the same circuit under a new title. In pandemic treaty negotiations, trade dispute panels, and financial compliance regimes, access to decision-making is conditional on holding approved institutional credentials—membership in specific expert panels, sign-off from accredited bodies, or prior leadership within sanctioned governance networks. To understand this structure, we need to map how the system breeds, brands, and recirculates its custodians.

Recruitment Pipelines and Revolving Doors

The Operating Class is not born into position but cultivated through an interlocking set of pipelines spanning elite universities, fellowship networks, strategic consultancies, multilateral institutions, and corporate boards. These loops allow personnel to carry credentials and insider status across sectors without interrupting their upward trajectory. This “credential laundering” is mirrored in awards like the Nobel Peace Prize, which—again and again—serve more as political symbols than merit recognitions. Examples include Henry Kissinger’s controversial 1973 award amid the Vietnam War, and Barack Obama’s early-era prize in 2009—underscoring how the sovereign logic of credentialing often outlives the credentials themselves.

Political office, NGO leadership, corporate governance, and global administration become interchangeable stations—linked by shared protocols rather than sectoral boundaries.

Academic and Fellowship Track – Key universities operate as credential mills: Oxford, Cambridge, Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Sciences Po, and the London School of Economics feed into domestic policy circles and transnational governance. Rhodes, Marshall, Gates, and Fulbright scholarships act as conversion points, importing talent into imperial and post-imperial networks. Business and political foundations—Rockefeller, Ford, Carnegie, Soros’ Open Society—extend reach into soft power and philanthropic governance. Examples include Bill Clinton (Rhodes Scholar → US President), Susan Rice (Stanford, Oxford, Rhodes → US National Security Advisor), and Alexander Downer (Oxford, diplomat, intelligence liaison).

Consultancy and Financial Track – Firms like McKinsey, Boston Consulting Group, and PwC are proving grounds for restructuring, privatisation, and metrics-driven governance. Central banks, the IMF, World Bank, BIS, and investment houses—Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, BlackRock—rotate personnel between policy and capital flows. Examples: Mark Carney (Goldman Sachs → Bank of Canada → Bank of England → climate finance envoy → prime minister), Mario Draghi (Goldman Sachs → ECB President → Italian PM), and Sheryl Sandberg (World Bank economist → Google → Facebook COO).

· Health, Science, and Standards Track – WHO, Gavi, the Global Fund, and national health bureaucracies train administrators fluent in epidemiological modelling, procurement, and biosecurity law. Regulatory agencies like FDA, EMA, and Australia’s TGA produce compliance experts who later join pharmaceutical boards or global health partnerships. Examples: Jane Halton (Australian Health Secretary → WHO simulations → ANZ Bank board → Gavi chair), Margaret Chan (Hong Kong health director → WHO Director-General), and Scott Gottlieb (FDA Commissioner → Pfizer board).

Media and Cultural Track – Senior editorial and production roles in BBC, Reuters, The Economist, New York Times, and CNN deliver narrative operators into the policy sphere. A marked subset are ex-intelligence personnel: John Brennan (CIA Director → NBC/CBS analyst), Michael Hayden (NSA/CIA Director → CNN analyst), Philip Mudd (CIA/FBI → CNN commentator). Others come via think tank media units: Fareed Zakaria (Foreign Affairs → CNN), Nick Robinson (BBC political editor → direct link to UK political leadership).

Judicial–Legal Track – The operating class also recruits heavily from the upper tiers of the legal profession. Senior judges, international arbitrators, and high-profile human rights lawyers transition into the governance machinery of trade dispute panels, WTO appellate bodies, or corporate compliance boards. The shift from courtroom to policy chamber converts courtroom credibility into governance authority. Figures such as Amal Clooney (legal advocacy → UN and World Bank advisory), Geoffrey Robertson QC (legal → human rights → global tribunal appointments) and Gary Born (international arbitration → corporate and governance boards).

Energy–Climate–Infrastructure Track – Energy executives and infrastructure financiers are being redeployed into climate governance and ESG enforcement. Alumni of oil, gas, mining, and renewables firms use their technical and financial credentials to anchor climate diplomacy and regulatory design. Christiana Figueres (UNFCCC during the Paris Agreement → climate finance boards), Fatih Birol (OECD → head the International Energy Agency), and John Kerry (US Secretary of State → climate-linked trade and finance).

Philanthropy–NGO–Humanitarian Track – Major NGOs and philanthropic foundations function as feeder institutions for the operating class, producing leaders who later migrate into formal governance or corporate roles. Such actors carry the aura of civil society while advancing policy already aligned with elite consensus. Melinda French Gates (Gates Foundation → WHO and UN initiatives); David Miliband (UK politics → International Rescue Committee → WEF presence) and Winnie Byanyima (Oxfam → UNAIDS) illustrates the NGO-to-global-governance loop.

Technology–Cybersecurity–Surveillance Track – Big Tech and defence–tech contractors supply a steady stream of personnel to state security posts, AI regulation boards, and transnational data governance projects. These figures bring platform control expertise and intelligence–adjacent credentials into the rule-writing environment. Eric Schmidt (Google’s executive suite → US defence advisory boards), Alex Stamos (Facebook’s chief security role → US government cybersecurity panels), and Anne Neuberger (senior NSA leadership → White House as Deputy National Security Advisor for Cyber and Emerging Technology).

Military and Intelligence Track – Officer academies (Sandhurst, West Point, ADFA) and specialist colleges (NATO Defence College) deliver personnel into command structures that translate into strategic policy and corporate roles. Examples: David Petraeus (US Army → CIA Director → KKR partner), Sir Alex Younger (MI6 Chief → corporate cyber adviser), and Leon Panetta (CIA → US Secretary of Defense → think tank head). Intelligence veterans feed into risk management firms, arms industry boards, and defence think tanks, carrying crisis-response logic and threat framing into civilian governance.

Across all tracks, fellowships, advisory boards, and visiting professorships act as credential laundries—turning political loyalty or operational skill into the formal qualifications needed for the next tier. Whether starting in academia, finance, health, media, or military, the outcome is a cadre fluent in harmonised governance protocols, rotating endlessly without leaving the operating environment.

Subtypes of the Operating Class

The Operating Class does not form a single occupational category. Its members are distributed across multiple enforcement environments, each responsible for translating elite consensus into practical, measurable compliance. While they appear in different institutional uniforms, they operate inside the same credential-gated control loop described in Part 7.

The four dominant subtypes are:

Platform Executives – These actors sit at the junction of infrastructure and governance, controlling the systems through which information, identity, and access flow. Their portfolios extend beyond corporate profit into the modulation of permissible speech, the design of identity authentication protocols, and the embedding of algorithmic rules into daily life. Platform executives determine which narratives can circulate and which identities are validated, often in coordination with regulatory bodies they once served or will later join. Figures like Sheryl Sandberg (Meta), Eric Schmidt (Google), and Brad Smith (Microsoft) exemplify the overlap between corporate architecture and policy authoring. Their leverage is structural—users are bound by platform rules regardless of political persuasion, and dissent can be throttled by code rather than law.

Behavioural Architects – Behavioural architects build and maintain the conditioning environments that secure public compliance without overt coercion. They design public health messaging, manage “nudge units,” set HR and diversity–equity–inclusion (DEI) frameworks, and operate in zones where institutional culture is engineered from the inside out. Their influence rests on shaping perception, normalising desired behaviours, and reclassifying resistance as pathology or non-compliance. Jane Halton’s trajectory—from Australian public health bureaucracy through pandemic simulation to global health finance—illustrates how behavioural architecture is not confined to messaging but extends into funding design and operational doctrine. Anthony Fauci’s career, similarly, demonstrates how behavioural authority can be maintained across multiple administrations by controlling the evidentiary frame for acceptable health policy.

Narrative Engineers – Narrative engineers work upstream from behavioural architects, scripting the conceptual frames within which policy debates occur. They hold editorial control in major media outlets, direct cultural production, run communications for think tanks, and coordinate messaging campaigns that prepare the ground for later compliance enforcement. These actors are not journalists in the traditional sense but are curators of legitimacy—deciding which data is newsworthy, which voices are authoritative, and which stories are suppressed. The revolving door between media and politics—BBC executives entering government communication offices, former intelligence officers becoming network news commentators—ensures that narrative engineering remains harmonised with transnational governance priorities.

System Guardians – System guardians maintain the compliance infrastructure itself. They operate as regulators, auditors, and standards enforcers embedded in transnational frameworks. Their mandate is to certify alignment with pre-set protocols, whether in finance, climate, trade, or public health. System guardians are often invisible to the public yet are decisive in determining which organisations can operate, trade, or access capital. Mark Carney’s movement from central banking into climate finance governance demonstrates the role’s scope—codifying ESG metrics into the capital system so that access to funding is contingent on compliance with harmonised protocols. Ursula von der Leyen’s EU leadership exemplifies the guardian role in political form, enforcing policy convergence across 27 states while holding procurement and regulatory levers at continental scale.

These subtypes differ in domain and public profile, but each enforces the same underlying logic: alignment with the harmonised control stack is a prerequisite for access, legitimacy, and continued relevance.

Operating Class as a System, Not a List

The Operating Class cannot be reduced to a roster of names. Lists give the impression of completeness, but this cadre’s continuity depends precisely on its capacity to replace personnel without altering function. The same role—a regulator, platform chief, health envoy—can be filled by individuals with differing political brands, professional histories, or public demeanours, provided they operate within the credentialed network and execute the harmonised protocols. The system is defined less by its occupants than by the structural positions they inhabit and the enforcement routines they carry. Those named in Addendum 2 serve as proof-of-concept rather than an exhaustive directory, each illustrating how the role survives the person, and how the person survives by remaining in role, whatever its institutional wrapper.

Closing Vector – From Operators to Permanent Governance

As electoral politics recedes into performance and symbolic contest, the Operating Class holds the functional levers of governance. Their authority is not renewed at the ballot box but maintained through ongoing presence in credentialed circuits—boards, commissions, advisory panels, and treaty bodies. Because the protocols they enforce are transnational, their relevance survives national leadership changes, party shifts, and public backlash.

What they execute is not policy in the conventional sense but the maintenance of an operating environment: interoperable standards, data pipelines, and enforcement metrics that bind jurisdictions into the same runtime logic. The longer these conditions persist, the more governance becomes detached from any direct democratic recall, settling into a state where operational authority is permanent, and those who hold it are interchangeable functionaries of a system that no longer needs to announce itself.

If the Operating Class holds the levers of a system designed to metabolise any ideology and neutralise dissent inside its own channels, the only viable contest is not in seizing those levers—but in writing a code they cannot run. On to Part 9: The Oligarchic Class – Fabricated Wealth, Conditional Power

Acknowledgements

This essay is in dialogue with David Rothkopf’s Superclass: The Global Power Elite and the World They Are Making (2008) and Peter Phillips’ Giants: The Global Power Elite (2018), each mapping the transnational managerial stratum. Frames and concepts from Land, Yarvin, and Thiel are referenced across the Overlords series as diagnostic tools, repurposed to expose the structural logic, custodianship and continuity of the system—in no way should this be constructed as evidence of my support or advocacy for their positions.

Published via Journeys by the Styx.

Overlords: Mapping the operators of reality and rule.

—

Author’s Note

Produced using the Geopolitika analysis system—an integrated framework for structural interrogation, elite systems mapping, and narrative deconstruction.